How does housing affect health equity? Exploring how harnessing social determinants, data science and decision-making can support improved health equity in Africa

Authors: Blessing Mberu, Sheila Tlou, Jane Ambuko*

What determines one’s health and wellbeing? When we think about health, more often than not it is always associated with clinical health. However, there is a wealth of evidence to show that physical health and wellbeing are inextricably linked to how a person lives — the conditions in which they grow, learn, work, play and age. These conditions – which could be political, social or economic – are referred to as the social determinants of health (SDoH). Examples of SDoH include education, employment, socioeconomic status, neighborhood and physical environment and social support networks.

“ The health sector is unlikely to achieve significant strides towards better health for all in isolation from the broader social, economic and political environment. More cohesive and coordinated policies that advance social justice and equity are needed to meet the needs of our most vulnerable citizens.”

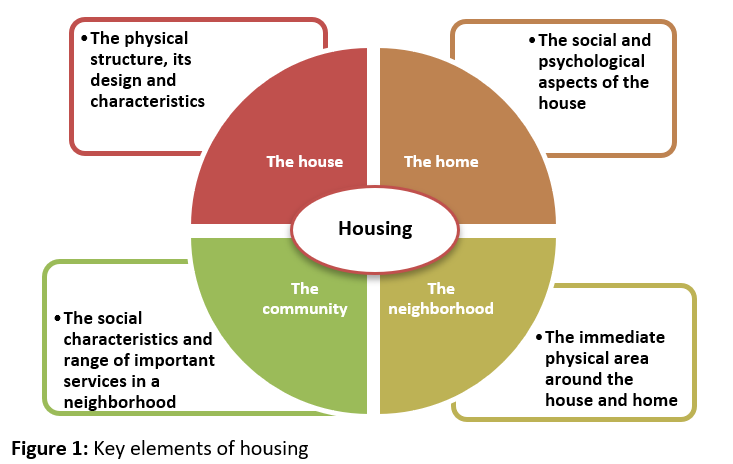

Housing is one example of a social determinant of health. So how does housing affect one’s health and the health outcomes of a population? Housing influences, and is influenced by, other determinants including income, education, culture, etc. Elements of housing that affect one’s health and wellbeing are illustrated in Figure 1.

Research has demonstrated a strong relationship between poor housing conditions (sanitation, crowding, air quality, inadequate ventilation, etc.) and poor health outcomes. Access to affordable and quality housing remains a major challenge in many cities in sub-Saharan Africa. This problem has been aggravated by the high urbanization rate with the urban population estimated to reach over 60% by 2050. African cities generally offer greater choices for housing, employment opportunities, and better services in education and health care, as compared to rural areas, but they also concentrate risks and hazards for health, further exacerbated by the inability of countries to provide basic social and economic infrastructure and opportunities. This results in the growth of slums and increasing urbanization of poverty. Consequently, the commonly assumed “urban advantage” in health and wellbeing has been compromised in many low- and middle-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

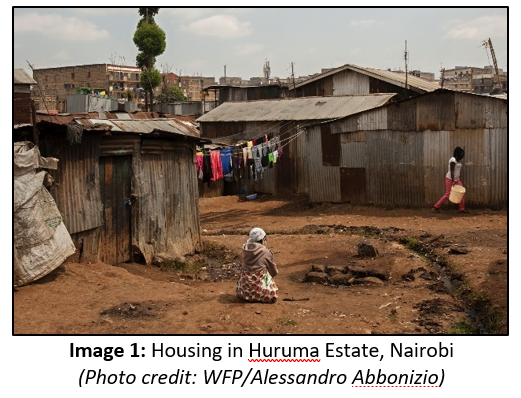

In Kenya, for example, the capital city of Nairobi is home to over four million people with an annual growth rate of 3.8%. It is estimated that up to 60% of Nairobi’s residents live in overcrowded informal settlements. These informal settlements are typically overcrowded with poor services and infrastructure. In many cases housing units that shelter entire families are rented single rooms constructed of iron sheets or mud (depicted in Image 1).

Such structures fall far short of meeting the key elements of housing described in Figure 1 above. The structures trap air pollutants and provide little protection from heat or cold. Access to safe water and sanitation tends to be grossly inadequate. Food insecurity is common, leaving children vulnerable to malnutrition and stunting. It should surprise no one that Kenyan slum dwellers have the worst health outcomes of any other population sub-group in the country.

Taking cognizance of the importance of quality and affordable housing, in 2017, the Government of Kenya (GoK) launched the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme (KENSUP) to address these and other inequities through a range of health and other social service programs. The government is working with the private sector and other partners to improve housing quality in the settlements and to build affordable housing in other parts of the country. These initiatives are a great start toward improving the health and wellbeing of the country’s most vulnerable citizens. In recent months and years, renewed efforts have been launched with many slum areas designated as special planning areas, with the aim of rallying an alliance of actors to work together in identifying challenges and co-creating solutions, ultimately transforming these settlements into planned, healthy, and functioning neighborhoods. Further, deepening affordable housing to enable ordinary Kenyans own a home is one of the four pillars of the GoK’s Big Four Agenda launched in 2017 over five years (2018-2022) to implement projects and policies that will accelerate economic growth and transform lives and improve the livelihoods of Kenyans in the short term. Other pillars of the agenda are universal healthcare, enhancing manufacturing, and attaining food security.

In these processes, a lot more could be achieved by taking stronger integrated approaches to solving these challenges – approaches that, among other things, recognize that housing policy is health policy, and embrace and leverage intersectionality to drive improvements in both sectors. Our understanding of just how and to what degree housing and other social determinants, such as education and income, influence health outcomes has progressed substantially in recent decades. At the same time, we’ve seen huge leaps in how health data are collected, analyzed, and used to inform action in the health sector. It is time to merge these two domains, to harness the best from both, and to accelerate the design and implementation of evidence-informed solutions.

This is the crux of a recently published report by the Commission on Health Determinants, Data and Decision-making (3-D Commission), an initiative by the Rockefeller Foundation and Boston University School of Public Health. Over the past two years, the 3-D Commission has delved into the key social and economic drivers that influence health outcomes and illustrates how data science and the social determinants of health should be integrated into decision-making processes. The findings of the 3-D Commission’s final report are centered around the need to consider the full spectrum of factors, barriers and opportunities for using data on determinants, and to use those data more systematically to inform policies and practices aimed at improving health across societies at different points in the development spectrum.

The impacts of social determinants are long term, dependent on context and intersect with other variables. Given the lengthy causal pathway between exposure to certain social factors and health outcomes — and all the intervening factors along the way — it can be difficult to quantify their effects. This is where the use of data becomes essential. Policymakers must continually connect the dots between epidemiological data and social determinants data to understand the health challenges they are facing more fully.

The 3-D Commission report provides a roadmap for scholars, practitioners and policymakers alike, with recommendations focused on three key areas — political will, technical capacity and community engagement — to drive results and improved outcomes. The report’s recommendations are rooted in six principles for action:

Evidence-informed decision-making to promote healthy societies needs to go beyond healthcare and incorporate data on the broader determinants of health.

All decisions about investments in any sector need to be made with health as a consideration.

Decision-making that affects population health needs to embrace health equity — while also acknowledging potential tradeoffs between short- and long-term costs and benefits.

All available quantitative and qualitative, national and local context data resources on the determinants of health should be used to inform decision-making about health.

Data on the social determinants of health should contribute to better, more transparent and more accountable governance.

Evidence-informed decision-making to promote healthy societies needs to be participatory and inclusive of multiple and diverse perspectives typified by the underlying vision of inclusion, participation and collaboration highlighted in the 2030 SDGs.

One key challenge to evidence-informed decision-making is a lack of appropriate data at local levels. Across SSA for example, national level datasets generally produce national indicators that blur inter- and intra-sub-group inequities and often lack aggregation at local levels, which is where the needs are located. Consequently, urban health programming lacks adequate urban health statistics that are needed by implementing agencies and local governments to identify priorities, measure the progress of interventions, and inform policies and future action. To address this gap, investments in and by local institutions in data collection and evidence generation at local levels have been imperative and will continue to support efforts to enhance evidence-based policy and action. In Kenya for instance, the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), designed and implemented the Nairobi Cross-sectional Slums Surveys (NCSS) in 2000 and 2012. Evidence from both surveys highlighted the living conditions of the urban poor across all slum settlements in the city, showing excess mortality and disease burden compared to any other subgroup in the country, limited access to health care services, and their debilitating physical environment, as well as changes over the inter-survey period. Further, the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS) was established in 2002 in two slum communities in Nairobi city, Korogocho and Viwandani, to provide a longitudinal platform to investigate the long-term social, economic, and health consequences of urban residence, focusing specifically on the needs of the urban poor. This platform has highlighted the plight of these populations and has deepened our understanding of changes and continuities in both determinants and strategies to improve their health and well-being.

It is time therefore to take these local initiatives and efforts to the next level by better mainstreaming the incorporation of data science and the social determinants of health into decision-making processes. In the search for pathways to health equity and wellbeing, Kenya and other countries across the region must continue to build their data systems to improve decision-making on these issues by incorporating insights from social determinants and big data more systematically. The health sector is unlikely to achieve significant strides towards better health for all in isolation from the broader social, economic and political environment. More cohesive and coordinated policies that advance social justice and equity are needed to meet the needs of our most vulnerable citizens.

*Blessing Mberu is Head of Urbanization and Wellbeing, African Population and Health Research Center; Sheila Tlou is Co-Chair, Nursing Now and Co-Chair, Global HIV Prevention Coalition; and Jane Ambuko is Associate Professor and Head of Horticulture Unit at the Department of Plant Science and Crop Protection, University of Nairobi.